When Ed Catmull, a co-founder of Pixar Animation Studios, addressed the Class of 2015 at Johns Hopkins University, he urged new graduates to broaden their view of creativity by accepting that mistakes and “dumb ideas” are necessary—even desirable. Many people ask how to become more creative, Catmull said. “I think this is the wrong question. The question is: What are the cultural and interpersonal forces that block creativity and change?” Because “new ideas are fragile and often off track,” Pixar long ago vowed to protect people who were “working on something that didn’t work…while they searched for something but didn’t know what it was.” In order to facilitate a creative dynamic, Pixar—and now Disney, which acquired Pixar—holds creative sessions called The Braintrust, where directors, animators and writers convene to help each other. Braintrust gatherings, Catmull explained, are structured as peer-to-peer dialogues, with the power structure removed from the room. Everyone gives and listens to honest notes, and everyone shares ownership of success. “Dumb ideas” are welcomed, because they often lead to good ideas. We agree with Dr. Catmull that this kind of candor-filled, listening-oriented, respectful communication “can lead to magic.” As Catmull said, “You feel the ego disappear. All attention is on the problem.” We want to hear: What does your organization do to foster creative collaboration? To join the conversation, click "comments" on our Community of Practice Forum.

0 Comments

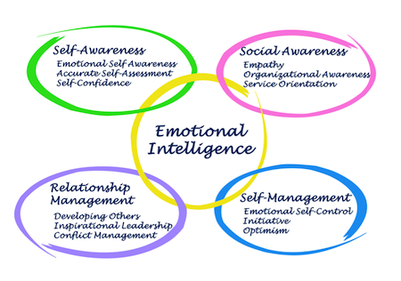

How should a manager react when an employee makes a mistake or underperforms? Some managers reprimand; others show curiosity (how did this happen?) and compassion (how can I help you through this?). Research cited by Emma Seppala, PhD, a Stanford University research psychologist writing in the Harvard Business Review, shows the compassionate response yields more positive outcomes. In particular, a study by Jonathan Haidt of NYU shows that the more employees look up to their leaders and are affected by their kindness and compassion (a state he calls elevation), the more loyal they become. And the results magnify: When compassionate behavior is shown toward one employee, anyone who has witnessed that behavior may also experience elevation and feel more devoted. It’s not always easy to show compassion when we are frustrated and under pressure ourselves, but we agree with Dr. Seppala, who recommends taking a moment to step back, detach, and then imagine what the other person might be experiencing. The resulting empathy can help you resolve the problem constructively. We want to hear: How do you handle it when someone makes a mistake? To join the conversation, click "comments" on our Community of Practice Forum.  Decades of research have shown EQ (Emotional Intelligence) to be a critical differentiator for leaders. EQ affects how we manage our own behavior and how we interact with others. In a recent Inc. article, Dr. Travis Bradberry, author of Emotional Intelligence 2.0, recounted the chief characteristics of people with high EQs and we were struck, once again, by how many of them are related to communication. Many aspects of EQ affect how we communicate with others. These include curiosity about other people, the ability to read others’ emotions, and a talent for neutralizing toxic people by not allowing their anger to fuel a tense situation. Other equally important aspects of EQ, however, affect how we communicate with ourselves. Those with high EQs have what Bradberry calls “a robust emotional vocabulary”— they can identify and differentiate among many subtle states of emotion. They can joke about themselves, let go of mistakes and grudges, and “stop negative self-talk in its tracks.” Whether your communication is internal or external, self-awareness and self-management are the keys to EQ, and to a high-impact life. We want to hear: What communication practices do you think are measures of EQ? To join the conversation, click "comments" on our Community of Practice Forum.  Can attaining a position of power actually interfere with the ability to empathize? Sadly, research says it does. Writing in the Harvard Business Review, Lou Solomon, CEO of the consultancy Interact, says this happens, “slowly, and then suddenly…with bad mini-choices, made perhaps on an unconscious level.” The powerful often become preoccupied with self-interest; simultaneously, they lose ability to read emotions and to adapt behavior to other people. In fact, power can actually change how the brain functions, according to research from neuroscientist Sukhvinder Obhi. The good news: All of this can be mitigated with self-awareness and self-management. We agree with Solomon, who recommends that those who want to avoid such counterproductive power traps remember to ask for feedback and be willing to risk vulnerability. Invite others to share the spotlight when things go well and take your share of the blame when they don’t. In the end, generosity and humility will inspire loyalty, trust and enthusiasm in those around you. We want to hear: Have you noticed a change in yourself or anyone else when promoted to a power position? How did you deal with it? To join the conversation, click "comments" on our Community of Practice Forum.  Jack Welch, former CEO of GE, once shared a “dirty little secret” about business: A certain quality can effectively chain an organization to mediocrity if it is not developed. That quality is candor. Likewise, Carlos Brito, CEO of InBev, says companies can never grow unless they face up to the negative truth as well as the positive. "I like people that can tell me the good and the bad with the same urgency and clarity," he says. Hudl, a sports video software company based in Lincoln, Nebraska, has a system for honest feedback that they refer to as #RealTalk. It’s a phrase used to inspire genuine candor among the team. Hudl co-founder John Wirtz says RealTalk— one of six values read off at the start of each company retreat—has been “absolutely critical” to the company’s success. Not every company has a culture like Hudl’s, but every organization must recognize that candor is an art. While honest feedback about performance is imperative, “brutal” honesty that picks people apart is more demoralizing than enlightening. Getting the balance right ensures that trust will grow and that conflicts can be mined for their productive value. We want to hear: Does your workplace value candor, and how do you go about delivering honest feedback in a constructive way? To join the conversation, click "comments" on our Community of Practice Forum. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

Glaser & Associates, Inc.

Executive Offices 1740 Craigmont Avenue, Eugene, OR 97405 541-343-7575 | 800-980-0321 [email protected] |

© 2019 Glaser & Associates. All Rights Reserved.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed